A strategy for transferring spacecraft trajectories between flight mechanics tools, called Trajectory Reverse Engineering (TRE), has been developed[1]. This innovative technique has been designed to be generic, enabling its application between any pair of tools, and to be resilient to the differences found in the dynamical and numerical models unique to each tool. The TRE technique was developed as part of the NESC study, Flight Mechanics Analysis Tools Interoperability and Component Sharing, to develop interfaces to support interoperability between several of NASA’s institutional flight mechanics tools.

The development of space missions involves multiple design tools, requiring the transfer of trajectories between them—a task that demands a large amount of trajectory data such as frames, states, state and time parametrizations, and dynamical and numerical models. This is a tedious and time-consuming task that is not always effective, particularly on complex dynamics where small variations in the models can cause trajectories to diverge in the reconstruction process.

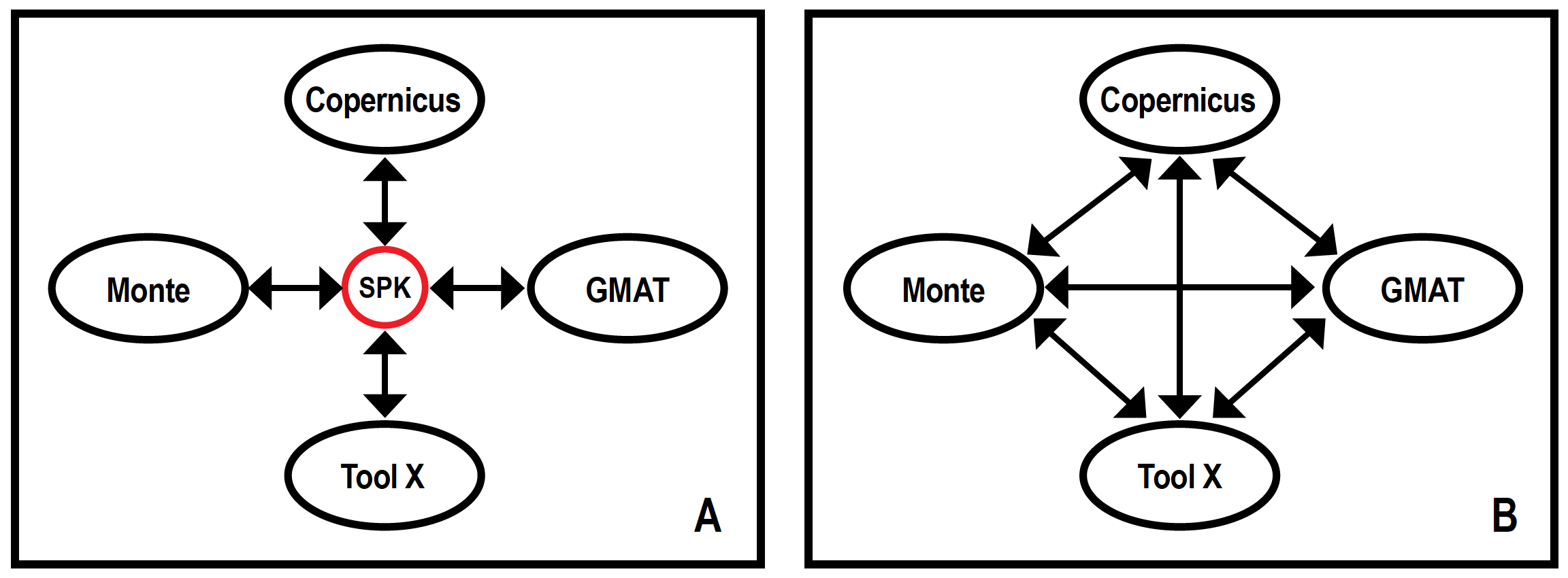

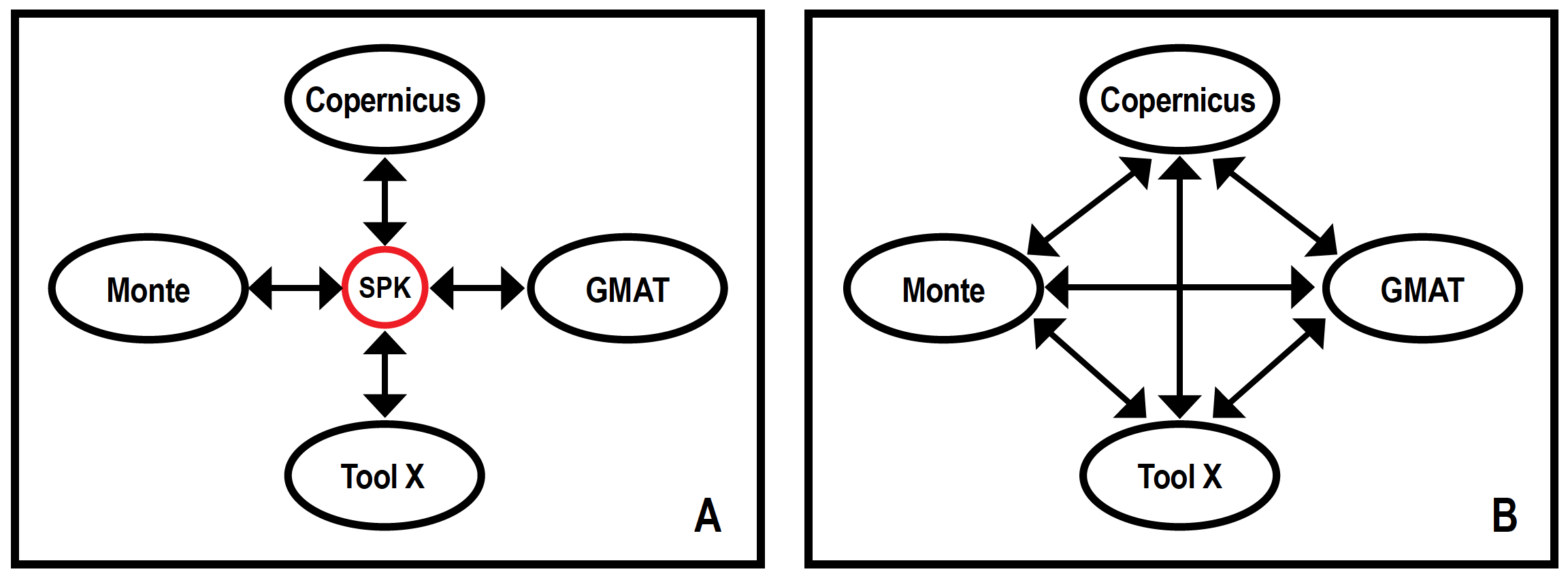

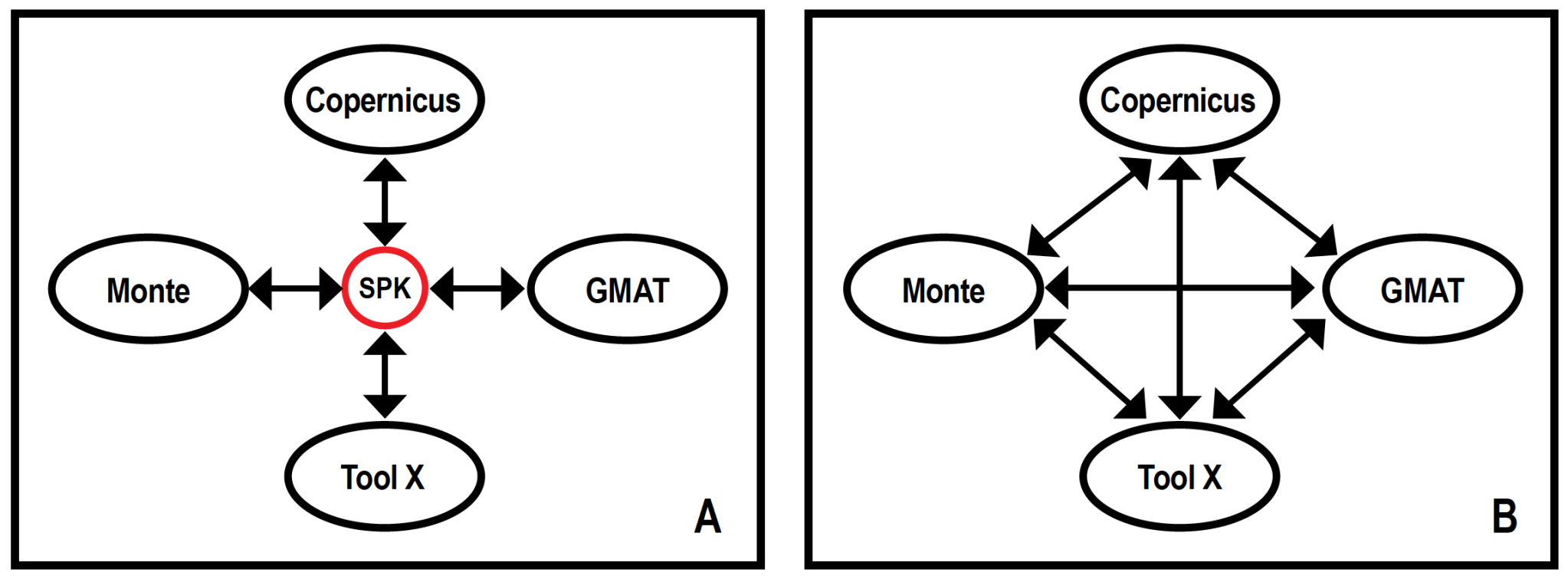

The TRE strategy is a trajectory-sharing process that is agnostic to the models used and performed through a common object: the spacecraft and planet kernels (SPK), developed at JPL Navigation and Ancillary Information Facility. The use of this common object aims to lay the groundwork for a global flight mechanics tool interoperability system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A) Interoperability between flight mechanics tools using standardized trajectory structures. B) Traditional specific tool-to-tool interface design. An SPK file serves as a container object, representing a trajectory as a 6D invariant structure in phase-space, agnostic to gravitational environments, fidelity models, or numerical representation of the system. A judicious kernel scan is used to recover the trajectory in any new tool, with the minimum (or no) information from the generating source. Impulsive maneuvers can be extracted in the form of velocity discontinuities, finite burns can be detected as variations on the energy of the system, and natural bodies conforming the trajectory universe can be directly read from the kernel.

Figure 1. A) Interoperability between flight mechanics tools using standardized trajectory structures. B) Traditional specific tool-to-tool interface design. An SPK file serves as a container object, representing a trajectory as a 6D invariant structure in phase-space, agnostic to gravitational environments, fidelity models, or numerical representation of the system. A judicious kernel scan is used to recover the trajectory in any new tool, with the minimum (or no) information from the generating source. Impulsive maneuvers can be extracted in the form of velocity discontinuities, finite burns can be detected as variations on the energy of the system, and natural bodies conforming the trajectory universe can be directly read from the kernel.

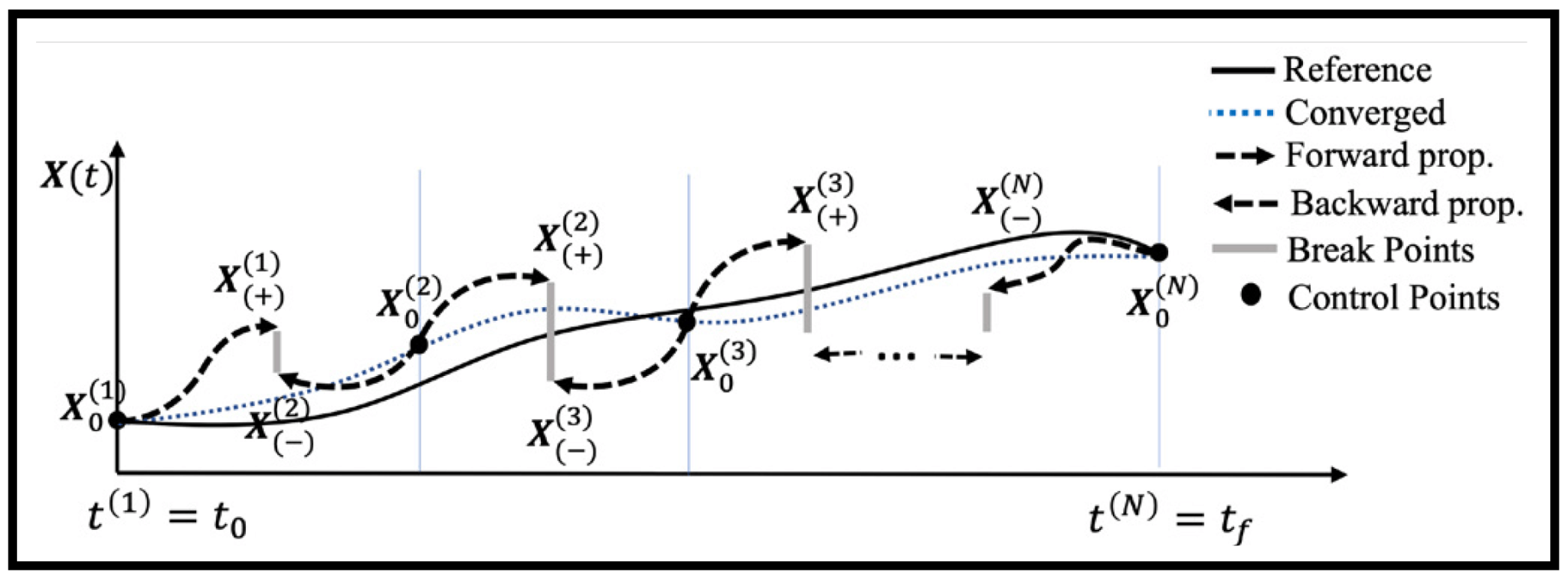

States or control points are found at predetermined time intervals or strategic points along the trajectory (e.g., periapsis, apoapsis, flybys closest approach), which are then used to reconstruct the trajectory timeline. The trajectory can be propagated forward in time using the selected set of control points. Due to the discrepancy between tool models, small or large discontinuities might appear between the integrated legs, which can be smoothed by the implementation of a multiple-shooting algorithm (Figure 2).

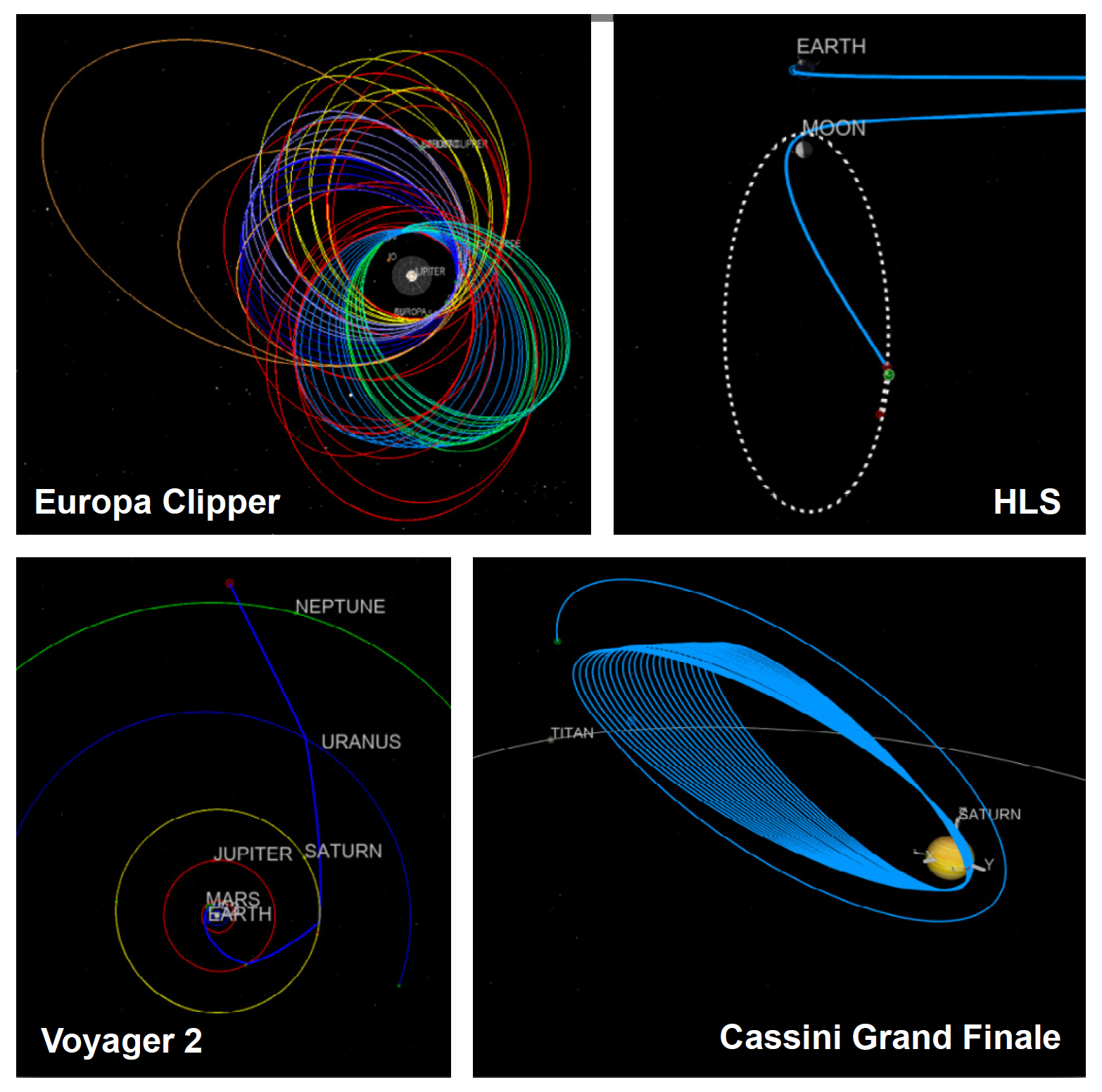

Figure 2. Multiple-shooting algorithm, utilizing strategic control points and a forward-backward propagation scheme. The TRE strategy was successfully implemented for Monte and Copernicus in the form of Python scripts (examples of reconstructed trajectories from SPK for each of these tools are shown in Figure 3). Through an optional user input file, a user can configure their specific problem. User-defined constraints are also possible, but their implementation would depend on the specific tool. The benefits of this effort include cost reduction through the sharing of capabilities, acceleration of the turnaround process involving various analysis tools at different stages of mission development, improved design solutions through multi-tool mission designs, and a reduction in development redundancy.

Figure 2. Multiple-shooting algorithm, utilizing strategic control points and a forward-backward propagation scheme. The TRE strategy was successfully implemented for Monte and Copernicus in the form of Python scripts (examples of reconstructed trajectories from SPK for each of these tools are shown in Figure 3). Through an optional user input file, a user can configure their specific problem. User-defined constraints are also possible, but their implementation would depend on the specific tool. The benefits of this effort include cost reduction through the sharing of capabilities, acceleration of the turnaround process involving various analysis tools at different stages of mission development, improved design solutions through multi-tool mission designs, and a reduction in development redundancy.

Reference:

Restrepo, R. L., “Trajectory Reverse Engineering: A General Strategy for Transferring Trajectories Between Flight Mechanics Tools” AAS 23-312, January 2023.  Figure 3. Future and flown missions reconstructions using Copernicus (Europa Clipper, Cassini) and Monte (HLS, Voyager 2) from SPK obtained from the Horizons System database at https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons/. For information, contact Heather Koehler heather.koehler@nasa.gov and Ricardo L. Restrepo ricardo.l.restrepo@jpl.nasa.gov.

Figure 3. Future and flown missions reconstructions using Copernicus (Europa Clipper, Cassini) and Monte (HLS, Voyager 2) from SPK obtained from the Horizons System database at https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons/. For information, contact Heather Koehler heather.koehler@nasa.gov and Ricardo L. Restrepo ricardo.l.restrepo@jpl.nasa.gov.