3 min read

Preparations for Next Moonwalk Simulations Underway (and Underwater)  Though the art of origami is centuries old, until the late 20th century it was considered virtually impossible to make insects or other figures with many long, complex protrusions. That changed with the introduction of math-based origami design, which Lang helped pioneer. Today, he’s still drawn to the challenges presented by insects and other arthropods, and they are well-represented in the menagerie of his origami gallery. After uncovering the mathematical underpinnings of origami, Robert Lang left a 20-year engineering career, including over four years at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, to pursue his lifelong passion. However, while he was working at JPL, Lang picked up an important key to computational design, allowing him to turn paper into impossibly intricate 3D forms.

Though the art of origami is centuries old, until the late 20th century it was considered virtually impossible to make insects or other figures with many long, complex protrusions. That changed with the introduction of math-based origami design, which Lang helped pioneer. Today, he’s still drawn to the challenges presented by insects and other arthropods, and they are well-represented in the menagerie of his origami gallery. After uncovering the mathematical underpinnings of origami, Robert Lang left a 20-year engineering career, including over four years at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, to pursue his lifelong passion. However, while he was working at JPL, Lang picked up an important key to computational design, allowing him to turn paper into impossibly intricate 3D forms.

In the center’s Micro Devices Laboratory in the late 1980s and early ’90s, Lang worked on building an optical computer that uses light rather than electricity to carry out calculations. This work introduced him to the concept of nonlinear constrained optimization.

Lang explained that a simple nonlinear constrained optimization problem is like packing different-sized balls into a box. The constraint is that the balls can’t overlap, and the solutions are nonlinear because the balls can be any direction or distance from each other. The optimization is making the box as small as possible.

System design optimization for lasers and other components requires minimizing energy consumption, semiconductor materials, and other costs. In origami, optimization means creating the most extensive form possible using a single sheet of paper.

In the mid-1990s, he took his expertise gain at JPL and created an open-source software called TreeMaker, the first program available to design complex origami figures. Lang’s design software uses an equation to map the points that will become features like a head and limbs. It helps decide exactly how far apart any two points have to be, depending on their location in the final shape.

In 2001, he left his last engineering job to become a full-time origamist, and he remains one of the world’s leading figures at the intersection of math and paper folding. Lang’s work ranges from small paper sculptures to huge public art made from metal and other materials, which he co-creates with other artists.

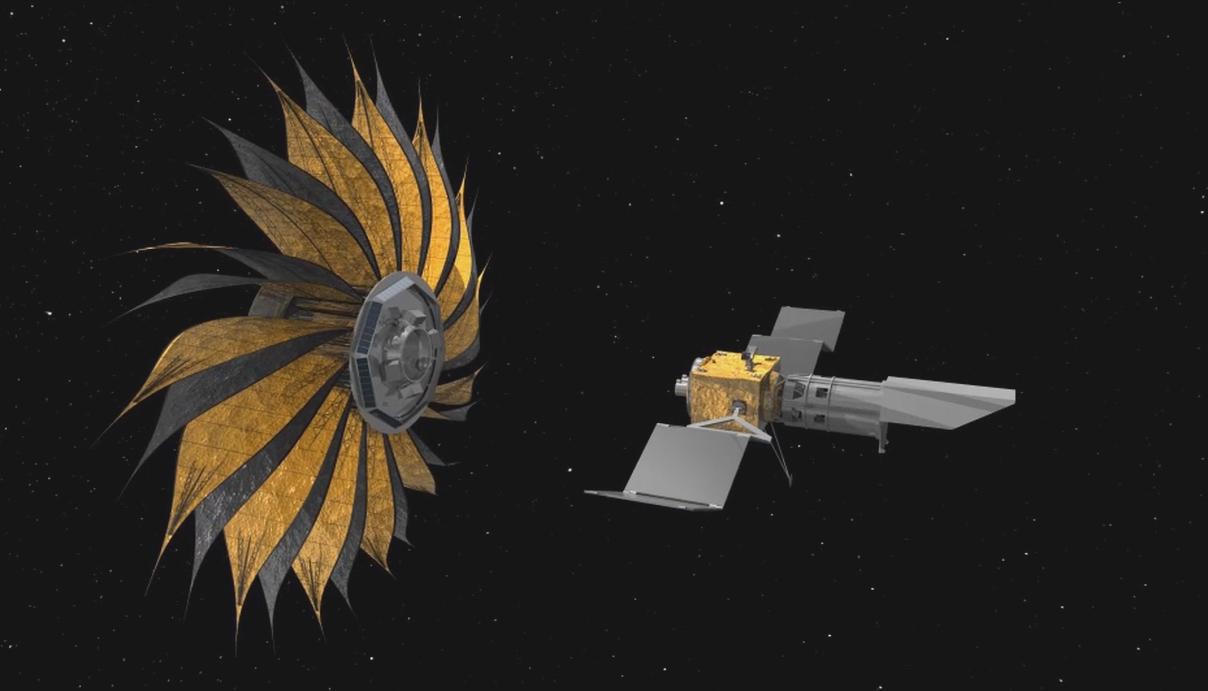

Since Lang left NASA, the agency has called him back in to consult on a few projects that capitalized on his dual background in engineering and origami. One of those was the Starshade concept, a design for a baseball diamond-sized disk that would fold up tightly to fit in a rocket fairing and then unfurl in space. There, it would block the light from a given star so a space telescope could photograph its planets. Credit: NASA The art of folding has even crept into space technology in recent years. Commercial companies now seek out Lang for his origami and engineering backgrounds to consult on folding hardware, including a collapsible radio antenna and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s Eyeglass space telescope. He’s also returned to NASA to help figure out how to fold large objects for launch inside rocket fairings.

Since Lang left NASA, the agency has called him back in to consult on a few projects that capitalized on his dual background in engineering and origami. One of those was the Starshade concept, a design for a baseball diamond-sized disk that would fold up tightly to fit in a rocket fairing and then unfurl in space. There, it would block the light from a given star so a space telescope could photograph its planets. Credit: NASA The art of folding has even crept into space technology in recent years. Commercial companies now seek out Lang for his origami and engineering backgrounds to consult on folding hardware, including a collapsible radio antenna and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s Eyeglass space telescope. He’s also returned to NASA to help figure out how to fold large objects for launch inside rocket fairings.

“The irony is that, when I was employed full-time at NASA, I was not working on origami, but after I left, I’ve been invited back a couple of times to work on origami-related projects,” he said.

Keep Exploring Discover Related Topics Missions

4 min read Media Get Close-Up of NASA’s Jupiter-Bound Europa Clipper Article 21 hours ago

4 min read Media Get Close-Up of NASA’s Jupiter-Bound Europa Clipper Article 21 hours ago  4 min read NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory Announces 3 Personnel Appointments Article 1 day ago

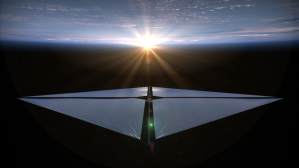

4 min read NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory Announces 3 Personnel Appointments Article 1 day ago  6 min read NASA Next-Generation Solar Sail Boom Technology Ready for Launch Article 2 days ago

6 min read NASA Next-Generation Solar Sail Boom Technology Ready for Launch Article 2 days ago