6 min read

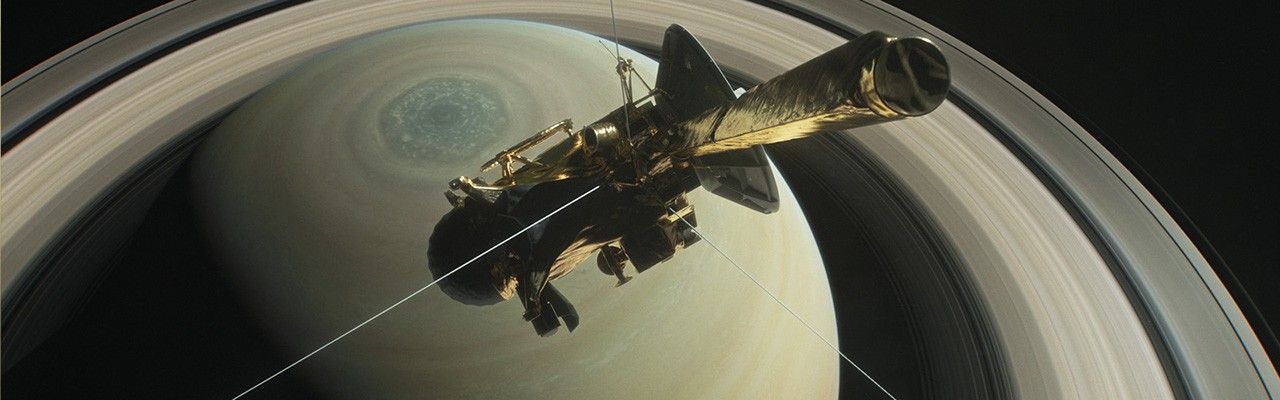

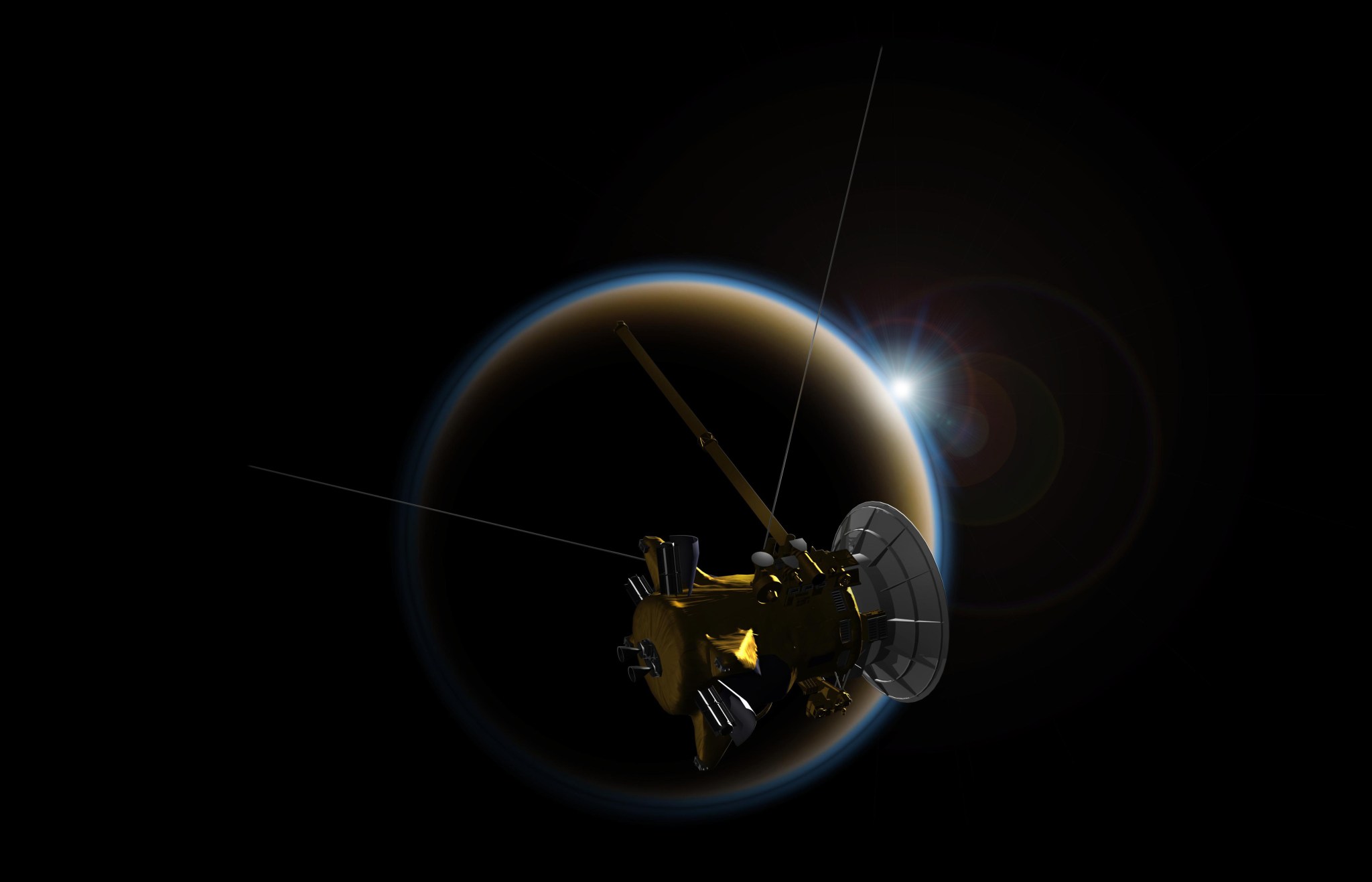

Preparations for Next Moonwalk Simulations Underway (and Underwater)  This artist’s concept depicts NASA’s Cassini spacecraft performing one of its many close flybys of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. By analyzing the Doppler shift of radio signals traveling to and from Earth, the mission precisely measured Titan’s gravity field.NASA/JPL-Caltech A key discovery from NASA’s Cassini mission in 2008 was that Saturn’s largest moon Titan may have a vast water ocean below its hydrocarbon-rich surface. But reanalysis of mission data suggests a more complicated picture: Titan’s interior is more likely composed of ice, with layers of slush and small pockets of warm water that form near its rocky core.

This artist’s concept depicts NASA’s Cassini spacecraft performing one of its many close flybys of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. By analyzing the Doppler shift of radio signals traveling to and from Earth, the mission precisely measured Titan’s gravity field.NASA/JPL-Caltech A key discovery from NASA’s Cassini mission in 2008 was that Saturn’s largest moon Titan may have a vast water ocean below its hydrocarbon-rich surface. But reanalysis of mission data suggests a more complicated picture: Titan’s interior is more likely composed of ice, with layers of slush and small pockets of warm water that form near its rocky core.

Led by researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, the new study could have implications for scientists’ understanding of Titan and other icy moons throughout our solar system.

“This research underscores the power of archival planetary science data. It is important to remember that the data these amazing spacecraft collect lives on so discoveries can be made years, or even decades, later as analysis techniques get more sophisticated,” said Julie Castillo-Rogez, senior research scientist at JPL and a coauthor of the study. “It’s the gift that keeps giving.”

To remotely probe planets, moons, and asteroids, scientists study the radio frequency communications traveling back and forth between spacecraft and NASA’s Deep Space Network. It’s a multilayered process. Because a moon’s body may not have a uniform distribution of mass, its gravity field will change as a spacecraft flies through it, causing the spacecraft to speed up or slow down slightly. In turn, these variations in speed alter the frequency of the radio waves going to and from the spacecraft — an effect known as Doppler shift. Analyzing the Doppler shift can lend insight into a moon’s gravity field and its shape, which can change over time as it orbits within its parent planet’s gravitational pull.

This shape shifting is called tidal flexing. In Titan’s case, Saturn’s immense gravitational field squeezes the moon when Titan is closer to the planet during its slightly elliptical orbit, and it stretches the moon when it is farthest. Such flexing creates energy that is lost, or dissipated, in the form of internal heating.

When mission scientists analyzed radio-frequency data gathered during the now-retired Cassini mission’s 10 close approaches of Titan, they found the moon to be flexing so much that they concluded it must have a liquid interior, since a solid interior would have flexed far less. (Think of a balloon filled with water versus a billiard ball.)

New technique The new research highlights another possible explanation for this malleability: an interior composed of layers featuring a mix of ice and water that allows the moon to flex. In this scenario, there would be a lag of several hours between Saturn’s tidal pull and when the moon shows signs of flexing — much slower than if the interior were fully liquid. A slushy interior would also exhibit a stronger energy dissipation signature in the moon’s gravity field than a liquid one, because these slush layers would generate friction and produce heat when the ice crystals rub against one another. But there was nothing apparent in the data to suggest this was happening.

So the study authors, led by JPL postdoctoral researcher Flavio Petricca, looked more closely at the Doppler data to see why. By applying a novel processing technique, they reduced the noise in the data. What emerged was a signature that revealed strong energy loss deep inside Titan. The researchers interpreted this signature to be coming from layers of slush, overlaid by a thick shell of solid ice.

Based on this new model of Titan’s interior, the researchers suggest that the only liquid would be in the form of pockets of meltwater. Heated by dissipating tidal energy, the water pockets slowly travel toward the frozen layers of ice at the surface. As they rise, they have the potential to create unique environments enriched by organic molecules being supplied from below and from material delivered via meteorite impacts on the surface.

“Nobody was expecting very strong energy dissipation inside Titan. But by reducing the noise in the Doppler data, we could see these smaller wiggles emerge. That was the smoking gun that indicates Titan’s interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses,” said Petricca. “The low viscosity of the slush still allows the moon to bulge and compress in response to Saturn’s tides, and to remove the heat that would otherwise melt the ice and form an ocean.”

Potential for life “While Titan may not possess a global ocean, that doesn’t preclude its potential for harboring basic life forms, assuming life could form on Titan. In fact, I think it makes Titan more interesting,” Petricca added. “Our analysis shows there should be pockets of liquid water, possibly as warm as 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit), cycling nutrients from the moon’s rocky core through slushy layers of high-pressure ice to a solid icy shell at the surface.”

More definitive information could come from NASA’s next mission to Saturn. Launching no earlier than 2028, the agency’s Dragonfly mission to the hazy moon could provide the ground truth. The first-of-its-kind rotorcraft will explore Titan’s surface to investigate the moon’s habitability. Carrying a seismometer, the mission may provide key measurements to probe Titan’s interior, depending on what seismic events occur while it is on the surface.

More about Cassini The Cassini-Huygens mission was a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency), and the Italian Space Agency. A division of Caltech in Pasadena, JPL managed the mission for NASA’s Space Mission Directorate in Washington and designed, developed, and assembled the Cassini orbiter.

To learn more about NASA’s Cassini mission, visit:

https://science.nasa.gov/mission/cassini/

News Media Contacts

Ian J. O’Neill

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-2649

ian.j.oneill@jpl.nasa.gov

Karen Fox / Alana Johnson

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1600 / 202-358-1501

karen.c.fox@nasa.gov / alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov

2025-142

Keep Exploring Discover Related Topics Titan Overview: Cassini at Titan Until the Cassini mission, little was known about Saturn’s largest moon Titan, save that it was…

6 min read NASA’s Perseverance Mars Rover Ready to Roll for Miles in Years Ahead Article 3 hours ago

6 min read NASA’s Perseverance Mars Rover Ready to Roll for Miles in Years Ahead Article 3 hours ago  6 min read NASA JPL Shakes Things Up Testing Future Commercial Lunar Spacecraft Article 1 day ago

6 min read NASA JPL Shakes Things Up Testing Future Commercial Lunar Spacecraft Article 1 day ago  3 min read One of NASA’s Key Cameras Orbiting Mars Takes 100,000th Image Article 1 day ago

3 min read One of NASA’s Key Cameras Orbiting Mars Takes 100,000th Image Article 1 day ago