The march to the first Moon landing took a giant leap forward in May 1969 with the successful completion of Apollo 10, essentially a dress rehearsal for the landing mission. During their eight-day flight, the all-veteran Apollo 10 crew of Thomas P. Stafford, John W. Young, and Eugene A. Cernan rehearsed nearly every aspect of the Moon landing with the exception of the landing itself, flying to within nine miles of the lunar surface. Their mission sorted many of the unknowns for the lunar landing. While Apollo 10 traveled to the Moon, workers at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida rolled Apollo 11 to its launch pad. The Apollo 11 astronauts continued training for their July Moon landing mission while workers across NASA continued other preparations for the historic flight.

Apollo 10

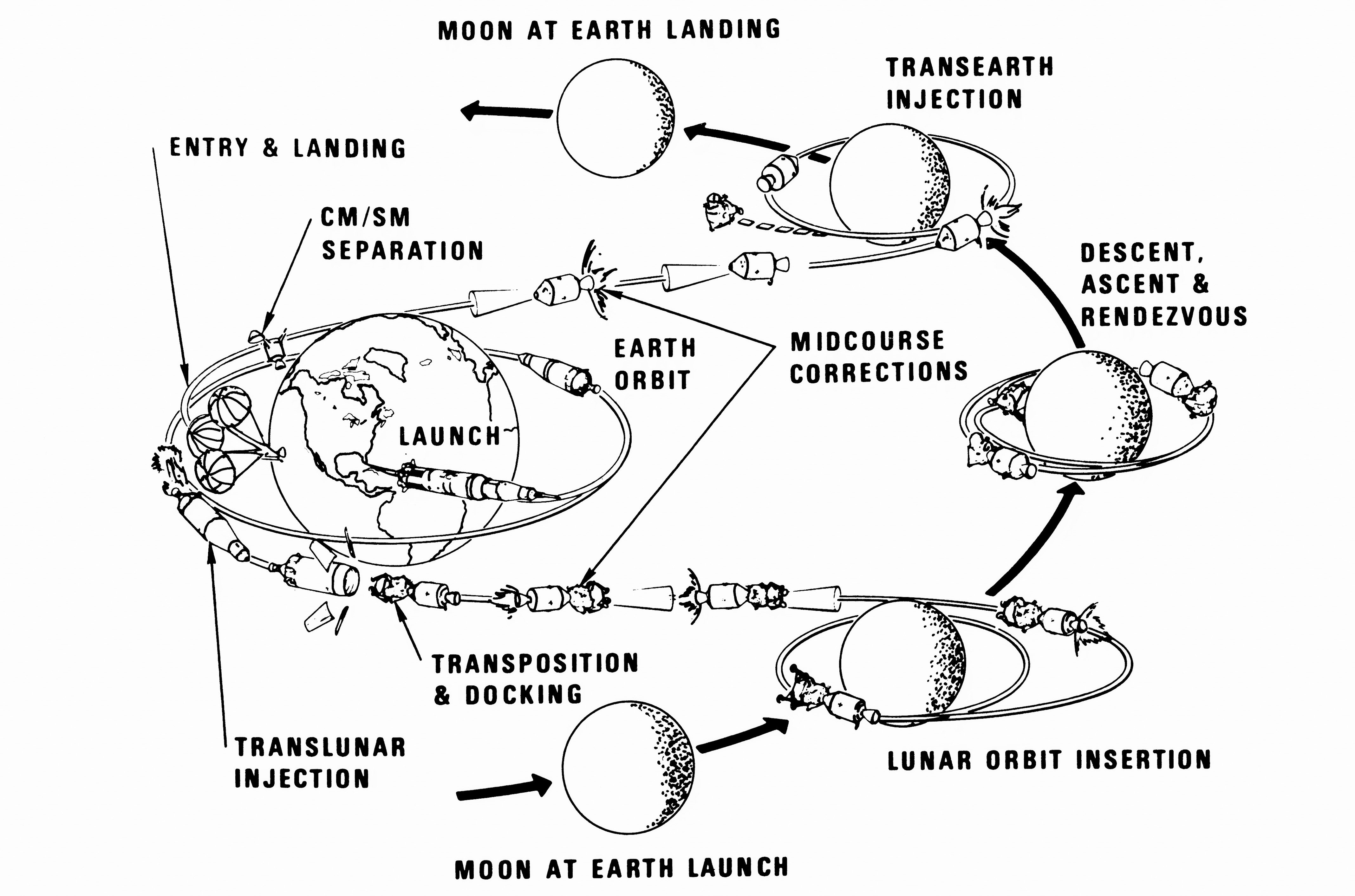

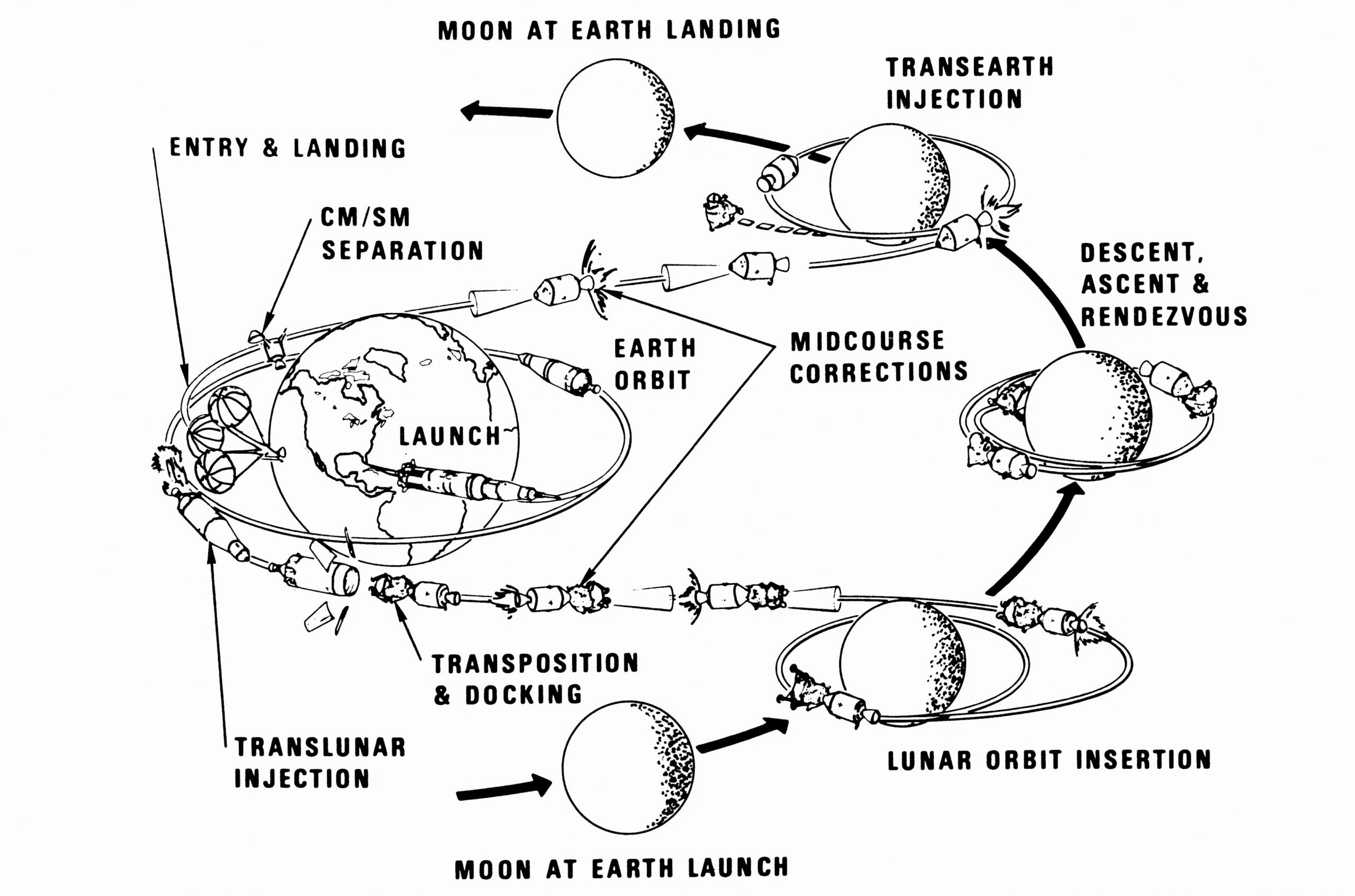

The Apollo 10 flight plan.

Designed as a final dress rehearsal for the Moon landing, the Apollo 10 mission plan replicated all aspects of that flight except for the landing itself. During the eight-day flight, Stafford, Young, and Cernan would spend three days traveling to the Moon before entering orbit around it. Stafford and Cernan would board the Lunar Module (LM) Snoopy, leaving Young aboard the Command Module (CM) Charlie Brown, and simulating a descent to the surface, fly to within 50,000 feet of the Moon. They would fly an approach to Apollo 11’s designated landing site in the Sea of Tranquility, photographing the area in as much detail as possible. After eight hours, Stafford and Cernan would rejoin Young. The primary goal of the mission accomplished, they would leave lunar orbit and travel back to Earth for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. Apollo 10 would address unknowns about navigation and communications required for a successful lunar landing.

Left: Astronaut-geologist Harrison H. Schmitt, second from left, provides geology instruction to Apollo 10 astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, left, John W. Young, and Eugene A. Cernan. Middle: The Launch Control Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida during the Apollo 10 Countdown Demonstration Test. Right: Cernan, left, Young, and Stafford pose in front of their Saturn V rocket.

During the final weeks before launch, Stafford, Young, and Cernan honed their skills in spacecraft simulators. They also received many hours of lunar geology instruction from experts, including Harrison H. Schmitt, the only geologist in the astronaut corps. At KSC, engineers completed the Countdown Demonstration Test on May 6, with Stafford, Young, and Cernan participating in the final hours, much as they would on launch day.

Left: Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, second from left, shares a laugh with Apollo 10 astronauts Eugene A. Cernan, left, Thomas P. Stafford, and John W. Young the day before launch. Middle: Stafford pats a giant stuffed Snoopy as he and Young and Cernan leave crew quarters for the trip to the launch pad. Right: Young, front, Stafford, and Cernan prepare to board the van for the ride to Launch Pad 39B.

Engineers began the countdown for Apollo 10 on May 13, as Stafford, Young, and Cernan finished their final simulator runs. Vice President Spiro T. Agnew joined them for dinner the night before launch. On launch day, they donned their spacesuits and boarded the van for the ride to Launch Pad 39B, where they climbed aboard their spacecraft.

Left: The official photo of the Apollo 10 crew of Eugene A. Cernan, left, Thomas P. Stafford, and John W. Young. Middle: The Apollo 10 crew patch. Right: Liftoff of Apollo 10.

Apollo 10 lifted off at 12:49 p.m. EDT, the only lunar mission to use Launch Pad 39B. The three stages of the Saturn V rocket performed flawlessly, placing Apollo 10 and its attached S-IVB third stage into a temporary parking orbit around the Earth. Two and a half hours later, after the ground and crew verified the normal functioning of all spacecraft systems, Mission Control called up, “10, you’re go for TLI,” the Trans-Lunar Injection. The S-IVB fired for 5 minutes and 43 seconds, sending Apollo 10 toward the Moon. The engine burned so precisely that Apollo 10 needed only one of the planned four midcourse corrections.

Left: Image of the rapidly receding Earth taken shortly after Trans-Lunar Injection. Middle: The Lunar Module Snoopy still attached to the S-IVB third stage during the Transposition and Docking maneuver. Right: A much smaller Earth taken late during the translunar coast.

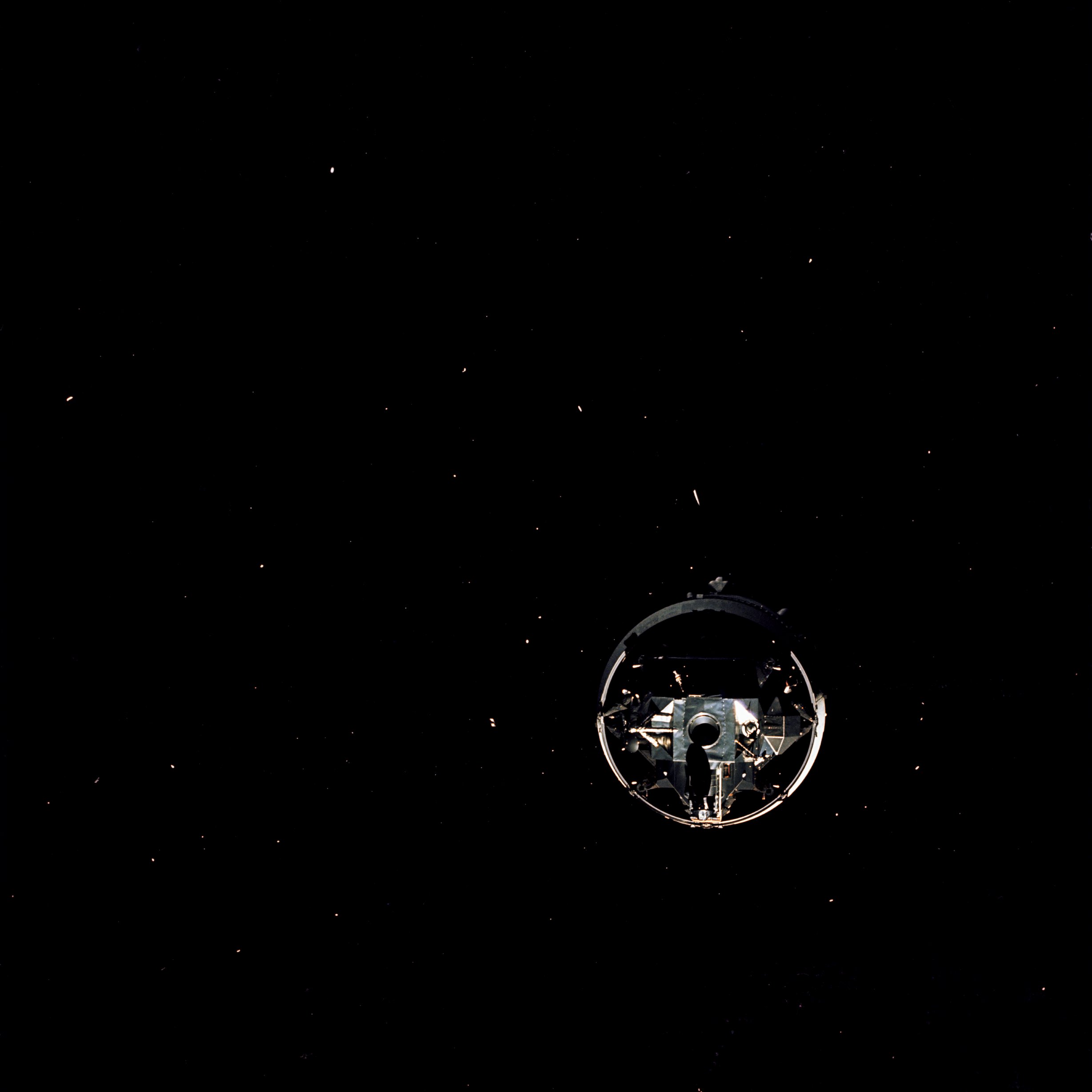

Thirty minutes after the TLI burn, the crew separated Charlie Brown from the S-IVB, with Snoopy still snuggled atop the third stage. Young guided Charlie Brown about 150 feet away, turned the spacecraft around, then flew it back to dock with Snoopy, completing the Transposition and Docking maneuver. Viewers received the first color TV images from space, the first of 17 transmission during the mission, showing Snoopy atop the S-IVB as Young brought Charlie Brown in for the docking. Thirty minutes later springs ejected Snoopy, now firmly docked with Charlie Brown, from the S-IVB, with Stafford exclaiming, “Snoopy’s coming out of the doghouse.” By this time, Apollo 10 had traveled more than 13,000 miles from Earth, with its velocity decreasing as the home planet’s gravity inexorably tugged at the spacecraft. The next two days passed without incident, with the astronauts performing routine navigation and housekeeping tasks and providing viewers at home more televised views of themselves and the receding Earth. About 62 hours after launch, they crossed into the Moon’s gravitational sphere of influence and their speed began to increase. Eleven hours later and still about 9,000 miles from the Moon, Apollo 10 passed into the darkness of the lunar shadow. Less than three hours later, Apollo 10 passed behind the Moon, cutting off communications with Earth.

Left: Earthrise as seen from lunar orbit. Middle: The Lunar Module Snoopy as seen from the Command Module Charlie Brown shortly after undocking. Right: Charlie Brown seen from Snoopy after undocking.

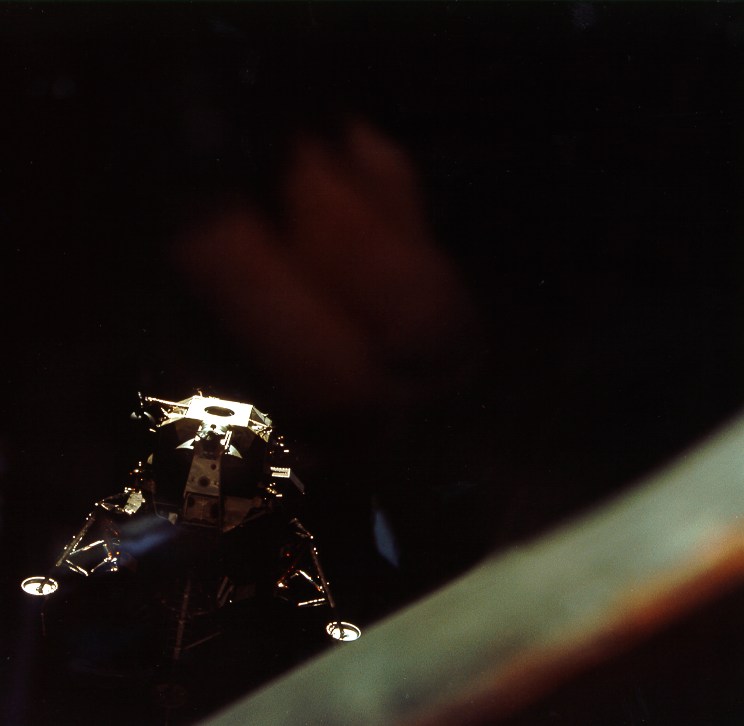

The Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI) maneuver, a six-minute firing of the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine, took place behind the Moon, placing Apollo 10 into an elliptical orbit. As they rounded the backside of the Moon, Stafford radioed to Mission Control, “You can tell the world that we have arrived.” All three crew members began excitedly describing the lunar scenery passing by beneath them, with Cernan summing it up best, “It might sound corny, but the view is really out of this world.” After two revolutions around the Moon, the astronauts once again fired the SPS engine, this time for 14 seconds, to circularize their orbit. Cernan opened the hatch to Snoopy for the first time, and floated inside to partially activate it, perform a brief inspection, conduct communications checks, and transfer equipment needed later during Snoopy’s free flight. Cernan reported on Snoopy’s condition, “I’m personally very happy with the fellow.” The crew prepared to settle down for their first night’s sleep in lunar orbit, with Cernan asking the ground to “watch Snoopy well tonight, and make him sleep good, and we’ll take him out for a walk and let him stretch his legs in the morning.” The next morning, all three crew members donned their spacesuits, Stafford and Cernan transferred to Snoopy, leaving Young in Charlie Brown, and then closed the hatches between the two spacecraft. Mission Control gave the crew the go to undock, and soon after Young separated the two spacecraft. Minutes later, with the two spacecraft flying separately, Snoopy began a slow roll so that Young could inspect and photograph the vehicle. Young then fired Charlie Brown’s thrusters to separate from Snoopy. And then, the time came to take Snoopy for a walk and let him stretch his legs, as Cernan had promised the night before.

Left: View of the Apollo 11 landing site in the Sea of Tranquility taken from the Lunar Module Snoopy during its close approach to the surface. Middle: Command and Service Module Charlie Brown as seen from Snoopy during the rendezvous and docking maneuver. Right: Snoopy as seen from Charlie Brown during the rendezvous and docking maneuver.

Mission Control gave Snoopy the go for the Descent Orbit Insertion burn of the LM’s Descent Propulsion System (DPS) engine to lower its orbital low point to about 50,000 feet. The 27-second burn began with the engine at 11.3% thrust for the first 15 seconds, then Stafford throttled it up to 40% thrust for the remainder of the maneuver. Stafford and Cernan began taking photographs and film of the surface as they started their descent to the low point, later calculated as about 47,000 feet. Cernan reported, “We is down among them,” referring to their low altitude over the lunar landscape. They successfully tested Snoopy’s landing radar, a critical test before the actual landing mission, all the while continuing a running commentary describing the landscape below them including all the landmarks leading up to the planned Apollo 11 landing site in the Sea of Tranquility. Stafford and Cernan then separated the LM’s ascent stage from the descent stage. During the staging, Snoopy experienced some unexpected motions in all three axes that Stafford and Cernan quickly brought under control. Investigators later attributed the gyrations to a switch placed in the wrong position. Ten minutes later, they fired Snoopy’s Ascent Propulsion System (APS) engine for 15 seconds that simulated a liftoff from the Moon, and began the rendezvous process to rejoin Young in Charlie Brown, using the same maneuvers as during a landing mission. Young completed the docking and Stafford exclaimed, “Snoopy and Charlie Brown are hugging each other.” Snoopy had been on a very long leash, travelling up to 390 miles from Charlie Brown, meeting all planned objectives during its 8-hour 10-minute solo flight. Soon, the crew opened the hatches between the two spacecraft and Stafford and Cernan rejoined Young in Charlie Brown, bringing with them cameras and exposed film. They then closed the hatches for the final time and bid farewell to Snoopy. Due to residual air pressure in the docking tunnel that couldn’t be vented, Snoopy departed at a higher than expected speed. Stafford commented, “Snoop went some place,” and Young added, “Man, when he leaves, he leaves.” To prevent an unwanted recontact between the two spacecraft, Snoopy fired its APS engine to fuel depletion, which sent it safely out of lunar orbit and into an orbit around the Sun. Cernan, perhaps feeling some guilt about disposing of Snoopy, said, “I feel sort of bad about that, because he’s a pretty nice guy; he treated us pretty well today.”

Left: The rapidly receding Moon shortly after the Trans-Earth Injection. Middle: Earth photographed during the trans Earth coast. Right: Apollo 10 on its three main parachutes shortly before splashdown.

During their 31st and final orbit around the Moon, the astronauts prepared the spacecraft for its next critical maneuver, the Trans Earth Injection (TEI), to propel them out of lunar orbit and back toward home. “Houston, we are returning to Earth!” With those words, Stafford announced that the TEI, a 165-second burn of the SPS engine had succeeded. The three-day return trip to Earth passed uneventfully, the crew conducting a single midcourse maneuver. As they approached the Earth, the crew separated the CM from the Service Module and turned its blunt heat shield into the direction of travel. By the time it made first contact with the Earth’s atmosphere 16 minutes later at an altitude of 400,000 feet, the point called Entry Interface, Apollo 10 had accelerated to 24,791 miles per hour, the fastest reentry for any crewed space mission. The spacecraft entered a radio blackout period a few seconds later, caused by the buildup of ionized gases as a result of rapid deceleration. At 24,000 feet altitude, two drogue parachutes deployed to provide initial deceleration, followed at 10,000 feet by the three main parachutes that provided a splashdown velocity of about 22 miles per hour.

Left: The recovery helicopter delivered Apollo 10 astronauts Eugene A. Cernan, left, Thomas P. Stafford, and John W. Young to the deck of the U.S.S. Princeton. Middle: Dignitaries greet Cernan, left, Stafford, and Young during their stopover in American Samoa. Right: Young, Stafford, and Cernan greet well-wishers upon their arrival at Houston’s Ellington Air Force Base.

At precisely 11:53 a.m. CDT on May 26, 1969, Apollo 10 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean 460 miles east of American Samoa. The splashdown occurred shortly before sunrise, just 1.5 miles from the targeted point and 3.3 miles from the prime recovery ship the U.S.S. Princeton (LPH-5). Stafford, Cernan, and Young had completed a flight lasting 192 hours and 3 minutes. Within 39 minutes, recovery forces delivered the trio to the deck of the Princeton, where the ship’s captain and dozens of cheering sailors greeted them. After a brief stay aboard the Princeton, Stafford, Cernan, and Young flew by helicopter to Pago Pago, American Samoa, where the governor, his wife, and 5,000 Samoan well-wishers greeted them. From there, they took a C-141 transport aircraft back to Ellington Air Force Base (AFB) in Houston, where they reunited with their families and a cheering crowd welcomed them home. Sailors offloaded the CM Charlie Brown from the Princeton in Hawaii on May 31. From there, workers flew it to Long Beach, California, on June 4, and then trucked it to the North American Rockwell plant in Downey to undergo postflight inspection. NASA transferred accountability for Charlie Brown to the Smithsonian Institution in April 1970, following which the United States Information Agency took it on a tour of Europe, including the Soviet Union, France, and The Netherlands. The Smithsonian loaned the spacecraft to the London Science Museum in January 1976, where it remains on display today.

Left: Meeting of the minds – the Apollo 10 crew debriefs the Apollo 11 crew. Middle: Stafford, left, Young, and Cernan brief reporters during their postflight press conference. Right: The Apollo 10 Command Module on display at the London Science Museum. Image credit: courtesy London Science Museum.

Apollo 11

Left: The Apollo 11 Saturn V leaves the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on its way to Launch Pad 39A. Middle: Apollo 11 at Launch Pad 39A. Right: Apollo 11 astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, left, Michael Collins, and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin pose with their Saturn V rocket.

While Apollo 10 headed for the Moon, on May 20 workers at KSC rolled the Apollo 11 Saturn V from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to Launch Pad 39A. Two days later, they rolled the Mobile Service Structure around the rocket and began integrated tests on the launch vehicle.

At the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Apollo 11 astronauts conduct vacuum runs in Chamber B of the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory. Prime crew members Neil A. Armstrong, left, and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, and backup crew members James A. Lovell, and Fred W. Haise.

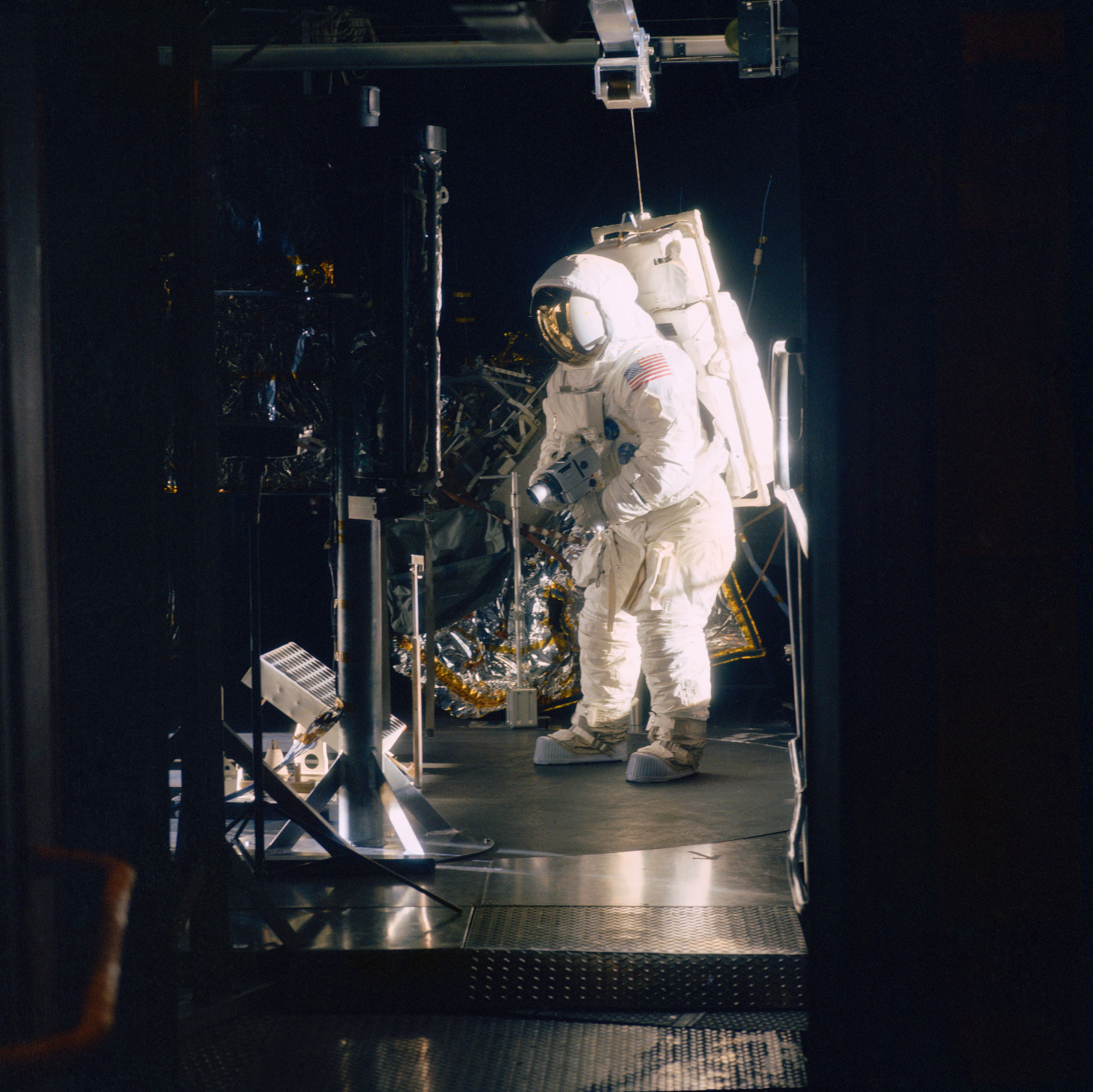

The Apollo 11 prime crew of Neil A. Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin and their backups James A. Lovell, William A. Anders, and Fred W. Haise continued training for the Moon landing. Armstrong, Aldrin, Lovell, and Haise each completed altitude runs in Chamber B of MSC’s Space Environment Simulation Laboratory. During these tests, the spacesuited astronauts practiced various lunar surface activities, such as activating the television camera, collecting rock samples, and deploying the scientific experiments of the Early Apollo Surface Experiment Package (EASEP).

Left: Neil A. Armstrong deploys the Passive Seismic Experiment Package. Middle: An Apollo 11 astronaut deploys the Laser Ranging Retro-Reflector. Right: Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin deploys the Solar Wind Collection experiment.

Armstrong and Aldrin practiced the deployment of the three scientific instruments they planned to deploy during their 2.5-hour surface excursion. Two instruments made up the EASEP – the Passive Seismic Experiment Package (PSEP), and the Laser Ranging Retro-Reflector (LRRR). The EASEP instruments remained on the surface after the astronauts departed, while the astronauts deployed and retrieved a third instrument, the Solar Wind Composition (SWC) experiment, during their spacewalk. The solar powered PSEP collected data to detect any possible moonquakes. Scientists used the passive LRRR to make precise measurements of the Earth-Moon distance. The SWC’s sheet of aluminum collected particles of the solar wind, in particular the noble gases helium, neon, argon, krypton, and xenon.

Left: Apollo 11 astronauts Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, left, Neil A. Armstrong, and Michael Collins aboard the MV Retriever prepare for the water egress test using the Biological Isolation Garment (BIG). Middle: Engineer John K. Hirasaki demonstrates the BIG. Right: Armstrong emerges from the boilerplate Command Module to join Aldrin and Collins, as recovery team’s decontamination office Clancy Hatleberg monitors the activity.

On May 24, the Apollo 11 astronauts rehearsed splashdown procedures in the Gulf of Mexico near Galveston, Texas, using a boilerplate Apollo CM and supported by the Motorized Vessel (MV) Retriever. The week before, NASA had decided that following splashdown, helicopter recovery forces would retrieve the astronauts from life rafts as on earlier missions. NASA rejected an alternative plan to have sailors aboard the carrier hoist the spacecraft with the astronauts inside onto the deck as too dangerous. Because the standard method would expose the astronauts to the air, raising the risk of contamination, the biological decontamination swimmer would give the astronauts Biological Isolation Garments (BIG) prior to their exiting the spacecraft after splashdown. For Apollo 11, the U.S. Navy’s Underwater Demolition Team-11 (UDT-11) assigned Lieutenant Clarence J. “Clancy” Hatleberg as the decontamination swimmer, and he joined Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin for the May 24 exercise. Exactly two months later, they would carry out the activity for real in the Pacific Ocean.

Left: The Mobile Quarantine Facility planned for Apollo 11 arrives at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Middle: NASA test pilot Harold E. “Bud” Ream flies the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle at Ellington Air Force Base to certify it for astronaut operations. Right: Lunar Module-2 during one of the drop tests at the Vibration and Acoustics Test Facility at MSC.

The next step in the quarantine process involved the astronauts entering the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF) aboard the recovery ship. The astronauts remained inside the MQF until delivered portside, from where a cargo jet would fly them back to Ellington AFB in Houston. From there, a truck delivered the MQF and the astronauts to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at MSC where they finished their 21-day quarantine. The MQF assigned to Apollo 11, the third of four units built, arrived at MSC on May 12. At Ellington AFB, MSC pilot Harold E. “Bud” Ream continued to fly the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle-2 (LLTV-2) to certify it for astronaut flights following the December 1968 crash of LLTV-1. Astronauts used the LLTV as a key training tool to simulate the flying characteristics of the LM especially of the final 500 feet of the descent. With astronauts still barred from flying the LLTV, they used the LLTV simulator and the Lunar Landing Research Facility (LLRF) at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, to practice the final descent to the surface. Once managers cleared the LLTV for astronaut use in early June, Armstrong and Lovell completed their training flights later that month. On May 7, in MSC’s Vibration and Acoustics Test Facility engineers completed drop tests using LM-2, certifying the LM and its systems for the loads they would encounter during a lunar landing.

Apollo 12

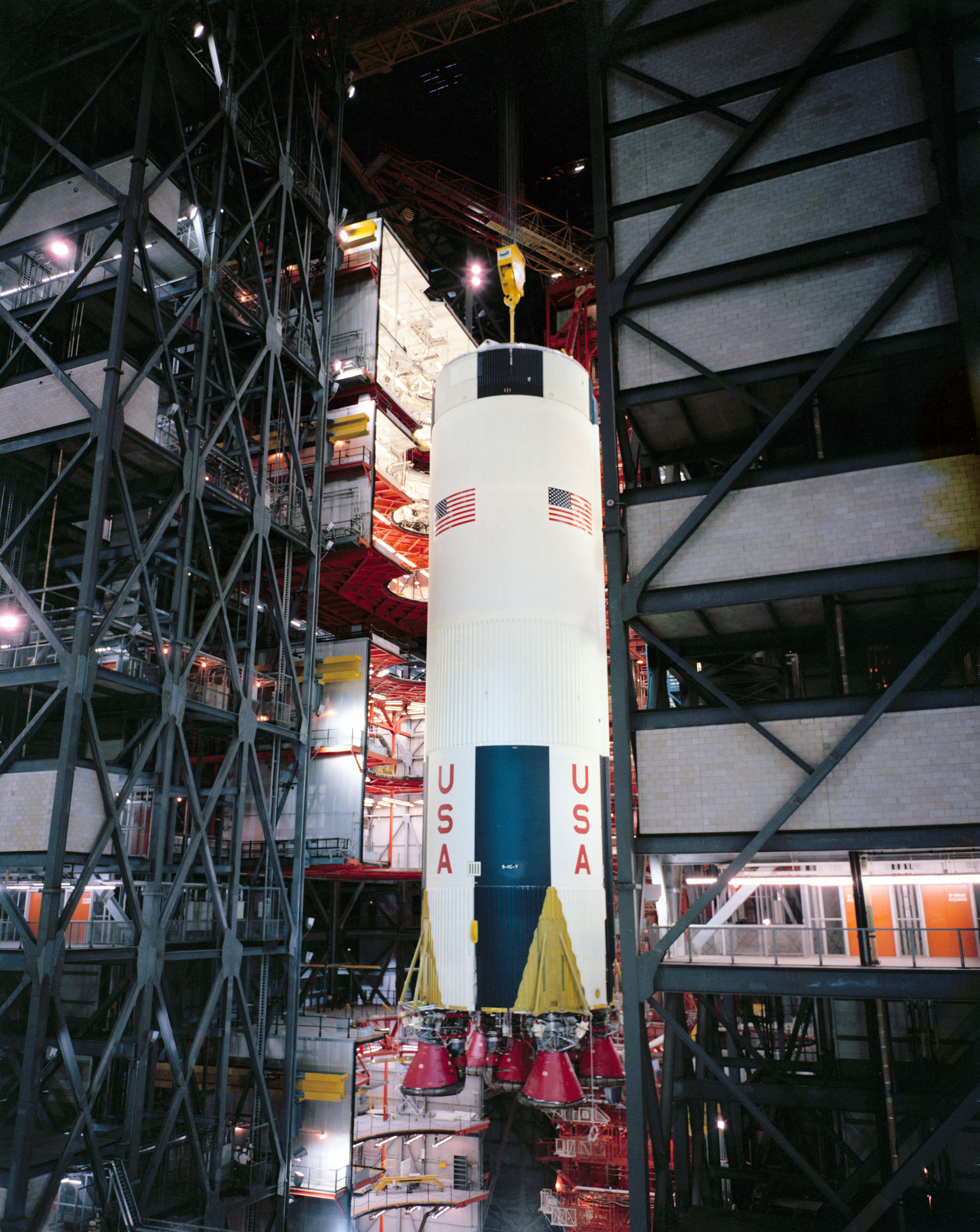

Left: In the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, workers lift the first stage of the Apollo 12 Saturn V rocket to begin the stacking process. Middle: Workers lower the second stage onto the first stage. Right: Workers have lowered the third stage onto stack.

While Apollo 10 headed for the Moon and Apollo 11 headed for its launch pad, workers prepared Apollo 12 for its eventual journey to the Moon, then tentatively planned for September. If Apollo 11 succeeded in its Moon landing mission, Apollo 12 would fly later, most likely in November. At KSC, the S-IC first stage of the Apollo 12 Saturn V arrived on May 3, joining the second and third stages already there. Workers in the VAB’s High Bay 3 stacked the first stage on its Mobile Launcher on May 7, added the S-II second stage on May 21, and the S-IVB third stage the following day. In the nearby Manned Spacecraft Operations Building, workers prepared the Apollo 12 CSM and LM for altitude chamber runs with the prime and backup crews, planned for June.

Left: Apollo 12 astronaut Charles “Pete” Conrad during the geology field trip to Big Bend, Texas. Middle and right: At the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Apollo 12 astronauts Conrad and Alan L. Bean conduct vacuum runs in Chamber B of the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory.

The Apollo 12 prime crew of Charles “Pete” Conrad, Richard F. Gordon, and Alan L. Bean and their backups David R. Scott, Alfred M. Worden, and James B. Irwin continued their training. Conrad and Bean, along with support astronaut Edward G. Gibson and several geologists, took part in a geology field trip to Big Bend, Texas, on May 1-2. During the two-day event, they simulated various lunar surface tasks to verify procedures, while receiving geology instruction along the way. Back at MSC, Conrad and Bean tested their spacesuits and spacewalking equipment and procedures in SESL’s Chamber B.

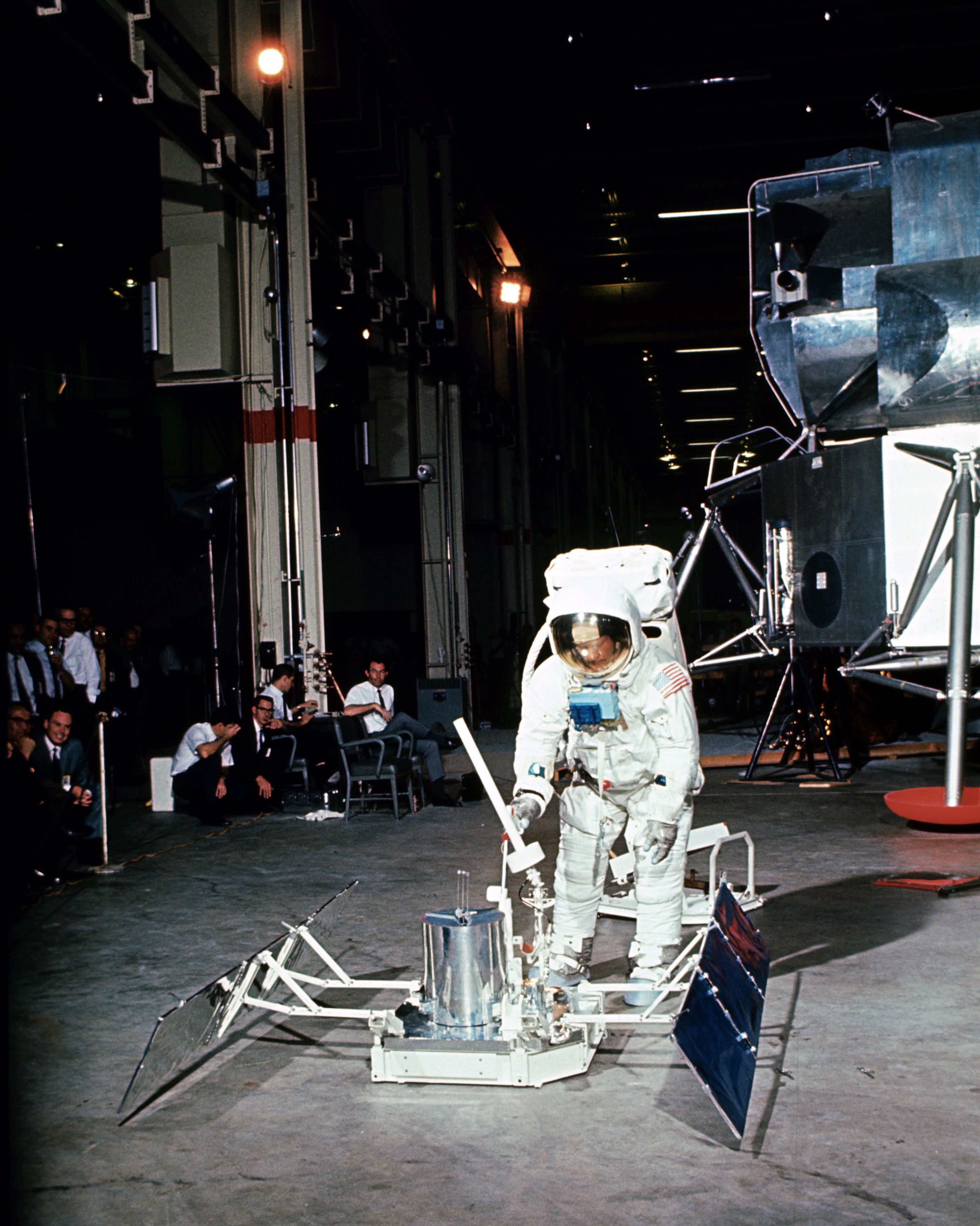

Left: Apollo 12 astronauts Alan L. Bean, left, and Charles “Pete” Conrad examine lunar surface science instruments. Middle: Apollo 12 support astronauts Gerald P. Carr, second from left, and Edward G. Gibson, right, assist Bean and Conrad in examining lunar surface science instruments. Right: Bean, wearing spacesuit at right, participates in procedures development for lunar surface activities.

The Apollo 12 mission plan called for two surface excursions and deployment of the first Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP), a more complex set of instruments than the Apollo 11 EASEP. Conrad and Bean completed their first examination of the hardware for the four ALSEP instruments planned for their mission.

In other NASA news:

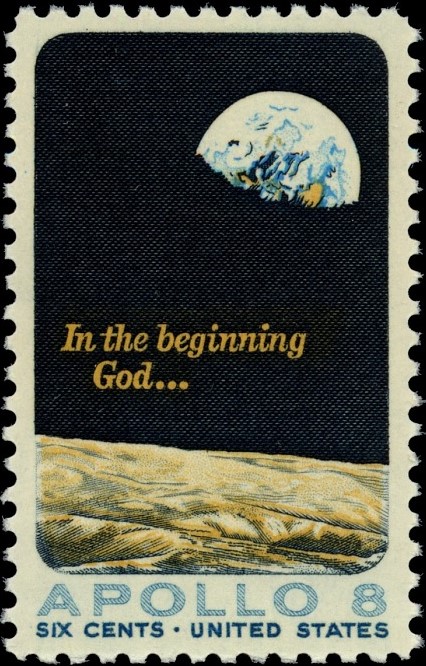

Left: U.S. postage stamp dedication to Apollo 8. Image credit: courtesy USPS. Middle: Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, left, James A. Lovell, and William A. Anders hold the Collier Trophy. Right: Borman narrates a film of the Apollo 8 mission at the COSPAR meeting in Prague.

On May 5, in a ceremony at the Rice Hotel in Houston, Postmaster General Winton M. Blount dedicated a postage stamp commemorating the Apollo 8 mission, presenting the first albums to the Apollo 8 crew of Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, and William A. Anders. Two days later, Borman, Lovell, and Anders accepted the Robert J. Collier award for their participation in the Apollo 8 mission.

On May 5, astronaut Alan B. Shepard marked the eighth anniversary of his suborbital Mercury-Redstone-3 mission aboard the Freedom 7 capsule. Two days later, Shepard had more reason to celebrate – flight surgeons returned him to full spaceflight status. Surgeons grounded Shepard in 1963 when he developed Meniere’s disease, an inner ear condition that causes dizziness. A minor operation in 1968 corrected the problem and Shepard remained symptom-free. Said Shepard of his return to flight status, “The sooner I get off the ground, the better.” He went on to command Apollo 14 in 1971, the only Mercury 7 astronaut to walk on the Moon.

On May 7, NASA established a task group to study development of a space station, headed by George E. Mueller, Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, with Apollo 8 astronaut Borman reporting to him as Field Director of Advanced Space Stations at MSC.

On May 16, President Richard M. Nixon nominated Apollo 8 astronaut Anders, also serving on Apollo 11 backup crew, as Executive Secretary of the National Aeronautics and Space Council, chaired by Vice President Agnew, effective in August, after Apollo 11 mission.

Between May 19-22, Borman attended the 12th annual meeting of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) in Prague, Czechoslovakia. He presented a film of the Apollo 8 mission and received a medal from the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences.

To be continued …

News from around the world in May 1969:

May 2 – The new cruise ship “Queen Elizabeth II” sets sail from Southampton to New York, marking first private use of Global Position System, relying on four U.S. Navy satellites.

May 5 – Milwaukee Bucs sign number one draft pick, UCLA center Lew Alcindor, who now calls himself Kareem Abdul Jabbar.

May 11 – British comedy group Monty Python forms.

May 16 – The Soviet Union’s Venera 5 spacecraft descends through Venus’ atmosphere, returning 43 minutes of data.

May 17 – The Soviet Union’s Venera 6 spacecraft descends through Venus’ atmosphere, returning data for 51 minutes.

May 19 – The Who release their rock opera album “Tommy.”

May 21 – President Richard M. Nixon selects Warren E. Burger as the next Chief Justice of the United States.

May 24 – The cartoon band “The Archies” release their song “Sugar, Sugar,” Billboard’s Song of the Year for 1969.

May 27 – Walt Disney World construction begins in Florida.

May 29 – Britain’s Trans-Arctic expedition makes first crossing of Arctic sea ice.

May 31 – Stevie Wonder releases the single “My Cherie Amour.”

16 min read 15 Years Ago: STS-125, the Final Hubble Servicing Mission Article 1 week ago

16 min read 15 Years Ago: STS-125, the Final Hubble Servicing Mission Article 1 week ago  11 min read 20 Years Ago: NASA Selects its 19th Group of Astronauts Article 2 weeks ago

11 min read 20 Years Ago: NASA Selects its 19th Group of Astronauts Article 2 weeks ago  14 min read 35 Years Ago: STS-30 Launches Magellan to Venus Article 3 weeks ago

14 min read 35 Years Ago: STS-30 Launches Magellan to Venus Article 3 weeks ago